“Design on Each Side for Waterwheel Worked by Donkey Power”, Folio from a Book of the Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices by al-Jazari (via Metropolitan Museum of Art) Whole cities of treasure were hidden under hills, guarded by golden automata. After the fall of Rome, tales spread through Europe that the treasures of the empire endured in great hoards beneath the earth. According to legend, the Cleveland table fountain survived only because it was buried in the palace gardens of Constantinople and unearthed centuries later.Īlthough that story is probably apocryphal, it echoes a genre of legends that feature automata lost underground. The rest have been lost, melted down into coin or scrapped and repurposed as parts of monstrances and reliquaries. These streams spin water wheels, ring silver bells, and fill the air with the sweet scent of rosewater.Īlthough table fountains were tremendously popular (Anne Boleyn presented one to Henry VIII that featured three nude woman with water pouring from their breasts), this is the only surviving example.

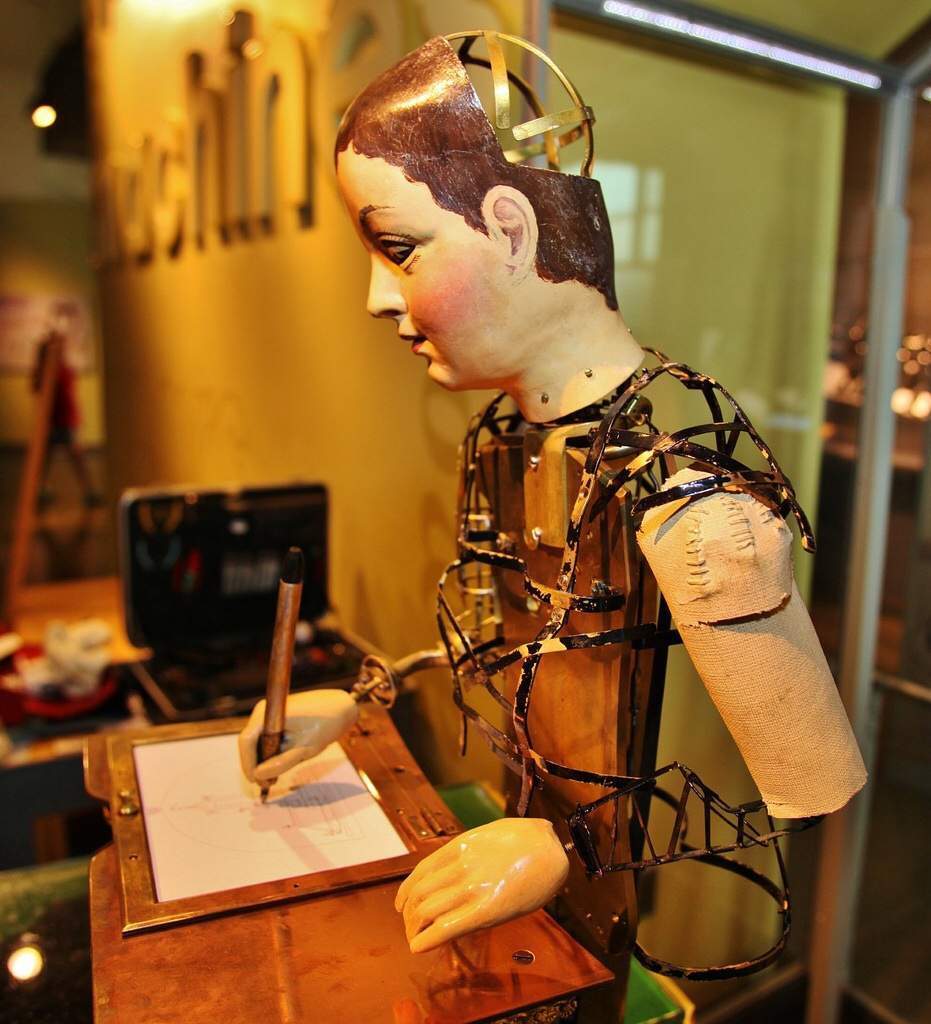

When it is in motion, water burbles up through the central tower, then gushes down through grimacing gargoyle mouths. Grotesques frolic over the colorful tiles on its sides. With its three layers of gold turrets and battlements, it looks rather like a Gothic wedding cake. Consider the table fountain now housed in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Table fountains, a popular medieval style of automaton, positively overflow with Jazari-like whimsy. Tales spread through Europe that the treasures of the empire endured in great hoards beneath the earth.Īl Jazari’s work was tremendously influential in the evolution of automata, in Europe as well as the Middle East. The peacock pours fresh water from its beak into a dish, triggering a door to swing open, which reveals a mechanical servant offering a dish of soap. Illustrated in rich jewel tones, the whimsical, intricate devices of this book act as microcosms, little worlds populated by miniature scribes, singers, dragons, elephants, and phoenixes, all interacting in Rube Goldberg chains.Īl-Jazari’s hand-washing device, for instance, looks like a tower with a bejeweled peacock perched on top. One of the most delightful and influential works on automata is The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, by Ismail al-Jazari. In medieval Cairo, they were a common feature of palaces-Al-Afdal Shahanshah, a Fatimid vizier, adorned his wine-hall with statues of singing girls, automata carved from camphor and amber that bowed when he entered the room and straightened up again when he took his seat. More often, they were intended to delight and entertain. Although it is just a trick, it still makes you shiver. There is a whiff of the supernatural here: The murdered dead rises to demand vengeance. It was this sight, in part, that spurred the onlookers to a bloody riot. Shakespeare immortalized Antony’s speech with the lines “Friends, Romans, countrymen,” but perhaps more striking than the words was the automata Antony used to illustrate them: A wax Caesar, rising from his deathbed and turning, slowly, to display his twenty-three bleeding wounds to the crowd.

This theme can be seen in one of the most iconic moments of Roman history, Mark Antony’s famous oration to the mob.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)